Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF) Energy Economics Analyst Galia Fazeliyanova says demand projections for LNG are forecasting 36% growth, reaching 5,460bcm by 2050.

Nevertheless, she cautions that:

- Continuing underinvestment or investment ‘gap’ in natural gas supply is one of the key drivers of the ongoing global energy crisis. It is the single largest risk to global energy security in the future.

- The upcoming 2023-2030 decade is considered a ‘golden age’ for liquefied natural gas (LNG) infrastructure deployment and investment. Therefore, timely execution and fast-track project development for LNG liquefaction and LNG regasification projects will be crucial for seizing the opportunity.

- After 2030, different regions worldwide may adopt diverging paths toward energy transition. Asia Pacific will keep moving towards a cleaner energy mix while balancing its economic and environmental priorities. Its’ expanding reliance on natural gas imports is a far-reaching opportunity as well as a challenge.

Introduction

The year 2022 was an exceptional one for the global natural gas trade in general and the LNG industry in particular, with many fundamental changes occurring due to the ongoing global energy crisis. In the new emerging natural gas trade pattern, as countries around the world continue to seek out reliable and affordable sources of energy, the demand for natural gas and LNG, based on the projections of the 2022 edition of the GECF Global Gas Outlook (GGO), is anticipated to grow by 36% in the long run, reaching 5,460 bcm by 2050. Therefore, investments in new gas infrastructure, particularly LNG, are expected to surge.

This expert commentary analyses the investment required for the midstream natural gas infrastructure – LNG liquefaction, LNG regasification and export pipelines – by 2050, enabling to sustain the GECF’s view on global natural gas trade.

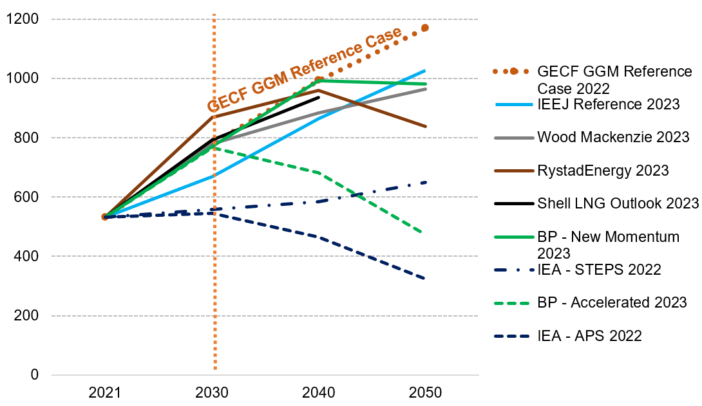

The year 2030 is anticipated to be a ‘boundary’ year for natural gas and LNG demand and trade globally. Before 2030, the natural gas trade looks very promising for all the world’s regions, and most of the gas industry stakeholders widely share this view. In the post-2030 era, the uncertainty for gas demand and trade grows as different regions worldwide might take diverging paths toward energy transition and decarbonisation [1]. Different industry forecasts in the long run show diverging trajectories for LNG demand reaching a wide range of 330 bcm – 1170 bcm by 2050 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. LNG demand forecasts (bcm)

Source: GECF Secretariat based on data from the GECF GGM

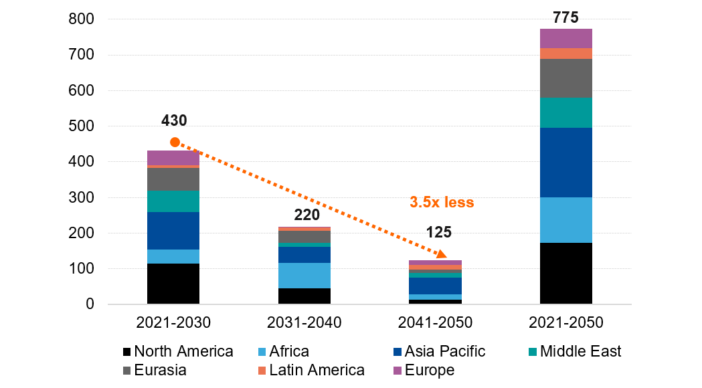

As per the 2022 GGO, the projected midstream natural gas investment from 2021 to 2050 is estimated to reach approximately US$775 billion. However, this investment will be unevenly distributed over the forecast period. The first decade, 2021-2030, is expected to see the allocation of over half of the total funding, amounting to around US$430 billion. This is primarily driven by the higher global demand growth for LNG, particularly in Europe during 2022-2030, and the increased LNG demand from the developing Asia Pacific region before 2030.

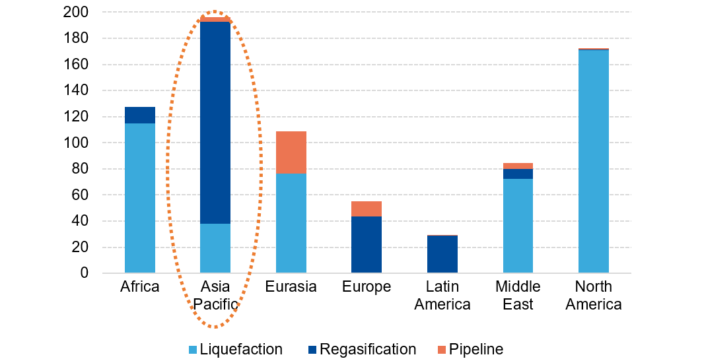

The commentary further explores the Asia Pacific region’s long-run trade and midstream natural gas investment prospects. The Asia Pacific region will remain the dominant long-term LNG market, primarily the Chinese, South and Southeast Asian nations leading the way [1] [8]. Its share of the LNG trade is expected to remain high at 66% of the global LNG trade by 2050 [1]. Therefore, Asia Pacific will champion natural gas infrastructure spending, with nearly US$200 billion or 25% of the global midstream investment in 2021-2050 [1]. At least 80% of this spending is forecast to be allocated to LNG regasification infrastructure.

Global and Asia Pacific gas trade

Global natural gas trade is expected to rise by 36% between 2021 and 2050, reaching over 1.7 tcm and accounting for the same share – almost one-third – of global gas demand as in 2021 [1]. LNG demand will accelerate further and more than double in volume, reaching 1.17 tcm (850 mt) or around 70% of the global natural gas trade by 2050. Moreover, the global LNG trade may overtake long-distance pipeline trade by 2026 [1], earlier than in GECF’s previous forecast, when LNG was planned to take over the pipeline trade in 2030 [2].

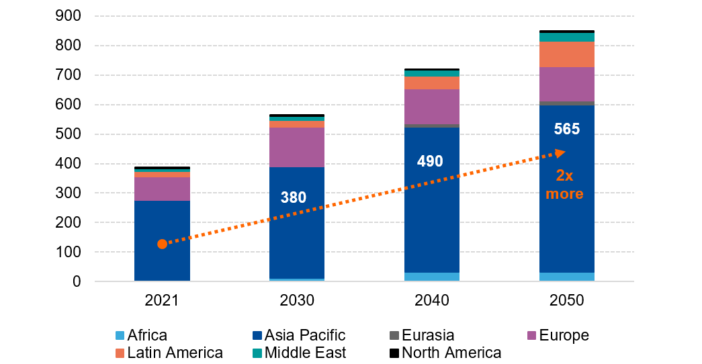

As a result of rapid economic growth and population rise, Asia Pacific natural gas demand has almost tripled in the past two decades, and the region has become the main global gas and LNG consumer. Additionally, Asia Pacific is projected to account for 30% of global natural gas demand in 2050, retaining the region’s leading role as the key LNG importer (Figure 2) [1]. Emerging Asian countries, primarily South and Southeast Asian nations, will lead that growth. The Asia Pacific region will continue to be a major player in the global LNG trade and its share is expected to remain high, accounting for 67% of the global LNG trade by 2050 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. LNG gross import by region (mt LNG)

Source: GECF Secretariat based on data from the GECF GGM

Global midstream natural gas investment

The midstream natural gas sector is poised for significant investment over the coming decades, spurred by increased demand for LNG originating from various regions around the globe.

Figure 3. Global midstream CAPEX by region (real US$ billion)

Source: GECF Secretariat based on data from the GECF GGM

The projected midstream investment of US$775 billion over the period from 2021 to 2050 underscores the pivotal role of natural gas in satisfying global energy requirements (Figure 3). The required level of investment is unevenly distributed over the forecast period.

Over a half, or US$430 billion, of gas industry midstream funding in 2021-2050 will be allocated solely in 2021-2030. The push for cleaner energy and the need for reliable and affordable energy to support sustainable economic development will be behind higher global LNG demand growth, particularly in Europe and developing Asia, before 2030.

In the later stage, in the 2030s and 2040s, the gas midstream funding may witness a precipitous decline. The existing infrastructure – European gas importing infrastructure by 2030 and LNG and natural gas pipeline receiving infrastructure in developing Asia by 2050 – may be sufficient to handle the expected gas demand by then, whereas further expansions may not be economically justified.

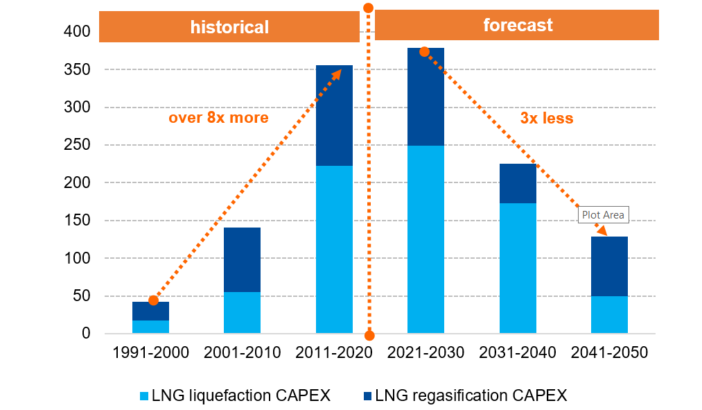

Figure 4. Historical and future global trends of LNG investment (real billion US$)

Source: GECF Secretariat based on data from the GECF GGM

Over the past three decades, worldwide investments in LNG infrastructure have experienced remarkable cumulative growth. In 2011-2020, total LNG liquefaction and regasification CAPEX surged more than eightfold compared to 1994-2000, rising from US$45 billion to US$355 billion. The two decades spanning from 2011 to 2030 can be characterised as a ‘golden age’ for LNG infrastructure investment, as LNG liquefaction and annual regasification expenditures will stay at US$350-375 billion (Figure 4). However, in the 2040s, the LNG industry funding will witness a sharp decline, dropping approximately a third of those seen in 2021-2030.

By 2050, no investment is anticipated in LNG infrastructure-related projects as countries across the globe ramp up their spending on low-carbon energy sources and infrastructure instead.

Midstream gas investment projects in the Asia Pacific

According to the 2022 GGO, the Asia Pacific region is expected to lead in natural gas infrastructure spending between 2021 and 2050. This region will witness the largest investment, accounting for nearly US$200 billion (Figure 5) or 25% of the total global midstream investment. A significant portion, approximately 80%, of this investment is projected to be allocated to LNG regasification infrastructure. This highlights the growing demand for LNG in the region.

Figure 5. Midstream gas investment by region 2021-2050 (real billion US$)

Source: GECF Secretariat based on data from the GECF GGM

Moreover, the Asia Pacific region is expected to maintain its position as the leading long-term importer of LNG. This is driven by the region’s rapid economic growth and rising demand for cleaner energy sources, which cannot be met solely through domestic natural gas production.

The global LNG regasification investment in Asia Pacific is undergoing a shift away from traditional legacy markets such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Instead, it is moving towards new markets, such as China, India, and developing South and Southeast Asian countries, as they strive to expand their regasification capacity. China emerged as the global leader in LNG imports in 2021, while its growth slowed down in 2022 due to stringent COVID restrictions, economic deceleration and elevated prices. On a similar ascending trajectory, India is experiencing a notable increase in LNG import and is making significant investment in regasification facilities. In line with this, India has unveiled a draft LNG policy that aims to more than double the regasification capacity to reach 100 mtpa by 2040 [1].

The share of LNG demand in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan is projected to decrease from 40% in 2021 to 18% by 2050, primarily driven by a reduced need for power generation in Japan. Conversely, South and Southeast Asia are poised to expand their share from 15% in 2021 to over 40%, emerging as the largest long-term demand bloc in the region. China is expected to be the dominant growth market this decade, with India assuming that role after 2030 [1].

The Southeast Asia region is anticipated to transition from net gas exporting to net importing in the mid-term, just before 2030. This shift is driven by the region’s growing demand for natural gas, fueled by economic expansion, urbanisation and rising living standards. The increased industrial activity and electricity needs in the region further contribute to the surge in gas demand [1]. Malaysia and Indonesia, in the long run, are projected to transition from being net LNG exporters to net importers as their domestic demand for natural gas surpasses their supply capabilities.

Over the past decades, Australia has experienced a significant increase in LNG exports, with a total LNG liquefaction capacity of 88 mtpa and LNG exports of 79 mt in 2021. However, in the longer term, Australia does not plan to expand its existing LNG liquefaction capacity. It will face challenges in maintaining its current level of LNG exports by 2050 as the country aims to phase out the majority of its coal-fired plants by the end of 2030. Additionally, domestic natural gas demand is expected to soar as a balancing factor in the transition from coal to renewable energy sources [7].

However, there are certain risks associated with the development of natural gas import and related infrastructure in Asia. Firstly, the gas markets in South and Southeast Asia are highly sensitive to prices, and the affordability of gas for these regions largely depends on future natural gas prices [4]. Secondly, in line with developed markets that have made clear commitments to achieving net-zero emissions, major developing Asian countries such as China, India and leading ASEAN member countries have also made similar pledges. This puts additional pressure on gas demand in the region in the long run. China sees its peak CO2 emissions before 2030 and aims to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, while India targets carbon neutrality by 2070. Consequently, as China and India are among the largest consumers of thermal coal globally, they will need to accelerate their transition and clean air policies, promoting the shift from coal and oil to gas across various sectors [1].

Long-term LNG purchasing agreements indexed to oil prices, typically spanning 15-20 years, serve as a mutual alignment of interests between producers and customers. These agreements offer producers a level of certainty regarding the recovery of significant upfront investments in LNG projects, while simultaneously ensuring a secure and reliable energy supply for many Asian importers.

Way Forward

The key stakeholders in the natural gas market should consider several practical considerations to strengthen the gas supply chain, particularly in relation to LNG.

Firstly, major natural gas and LNG producers should aim to operate at the lower end of the marginal cost curve for supplying to gas importing centres, such as Asian and European markets. Projects with economies of scale, such as Qatar’s North Field East Project, and cost-effective floating LNG solutions, as seen in the case of Mauritania-Senegal’s Tortue Floating LNG (FLNG), can improve cost efficiency [5]. Additionally, using modular liquefaction technology instead of conventional-designed trains can introduce flexibility to LNG projects that are time and cost-sensitive.

Secondly, natural gas and LNG producers should consider investing in downstream infrastructure, including import terminals, pipelines, and power plants, primarily in developing Asia. This will stimulate natural gas and LNG demand growth. Furthermore, a vertical integration strategy can benefit national oil companies and international oil companies in the natural gas supply chain, providing added value, increased profitability, and greater security for natural gas demand on both supply and demand ends.

Thirdly, market participants, such as energy companies or traders, can optimise profits by managing diversified LNG supply portfolios, optimising transportation cost savings, and enhancing flexibility alongside long-term contracts. This combination of long-term contracts and flexible portfolios provides stability and security of gas and LNG supply to the markets.

Lastly, natural gas and LNG producers and consumers should invest in technologies and options with the lowest CO2 emissions, including carbon capture, utilisation, and storage. Embracing energy-efficient equipment and reducing gas leaks will enhance competitiveness in the long run and contribute to decarbonising the energy sector. Mitigating the carbon footprint of exported LNG is expected to become a significant factor in its value and price as importing countries strive to meet climate commitments and CO2 emission targets.

Conclusion

By 2030, the outlook for the natural gas trade appears highly promising across all world regions. Key gas-importing countries are actively working towards securing reliable supply, leading to a surge in investments in new LNG infrastructure.

However, beyond 2030, diverging energy transition paths for each region could pose significant challenges, particularly for the Asia Pacific region, which is expected to remain the largest gas-importing region. In the 2030s and 2040s, investments in LNG liquefaction and regasification infrastructure are projected to decline substantially.

These developments present a dilemma for future gas investments as demand and trade predictions become increasingly challenging beyond 2030. Firstly, the natural gas investment pattern is cyclical [6], long-term, and capital-intensive, requiring substantial and long-term decision-making well in advance of gas production and transportation. Secondly, heightened natural gas price volatility and a structurally higher price level make funding decisions particularly difficult, especially considering the impact of inflationary pressures. Thirdly, escalating geopolitical turbulence and global fragmentation may lead to reduced investment allocation, including cross-border investments [3], and potentially increase the cost of capital. Lastly, the energy transition introduces further complexity and shortens the planning horizon for the gas industry [6].

The natural gas trade in the Asia Pacific is expected to continue expanding as natural gas demand grows steadily over the next three decades, with no peak in sight. Opportunities for natural gas to contribute to a more sustainable energy mix will emerge, especially if carbon capture and storage technologies become more widespread.

References

[1] GECF Global Gas Outlook 2022, January 2023

[2] GECF Global Gas Outlook 2021, February 2022

[3] Mario Catalán, Fabio Natalucci, Mahvash S. Qureshi, Tomohiro Tsuruga; Geopolitics and Fragmentation Emerge as Serious Financial Stability Threats; International Monetary Fund; April 5, 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/04/05/geopolitics-and-fragmentation-emerge-as-serious-financial-stability-threats

[4] International Energy Agency (IEA), Outlooks for gas markets and investment; April 2023; https://www.iea.org/reports/outlooks-for-gas-markets-and-investment

[5] McKinsey & Company, The future of liquefied natural gas: Opportunities for growth; September 21, 2020; https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/oil-and-gas/our-insights/the-future-of-liquefied-natural-gas-opportunities-for-growth

[6] Carole Nakhle, Oil and gas: The investment gap dilemma, GIS reports, February 3, 2023, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/oil-gas-investment/

[7] Rystad Energy, Australia’s energy trilemma: High stakes for global and local markets; April 28, 2023; https://clients.rystadenergy.com/clients/report?rid=372979&

[8] Wood Mackenzie, Global gas: Asia regional market report; April 2023; https://my.woodmac.com/document/150027510